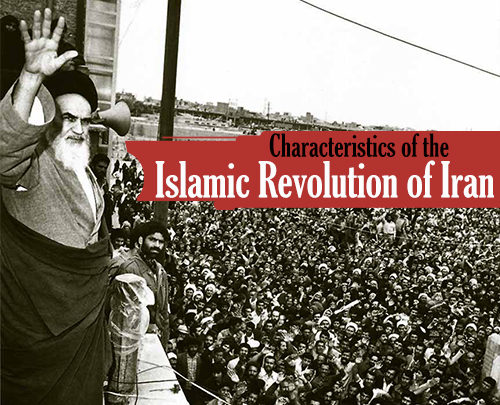

Conditions now seemed appropriate for Imam Khomeini to return to Iran and

preside over the final stages of the revolution. After a series of delays,

including the military occupation of Mehrabad airport from January 24 to 30, the

Imam embarked on a chartered airliner of Air France on the evening of January 31

and arrived in Tehran the following morning. Amid unparalleled scenes of popular

joy - it has been estimated that more than ten million people gathered in Tehran

to welcome the Imam back to his homeland – he proceeded to the cemetery of

Bihisht- Zahra to the south of Tehran where the martyrs of the revolution lay

buried. There he decried the Bakhtiyar administration as the “last feeble gasp

of the Shah’s regime” and declared his intention of appointing a government that

would “punch Bakhtiyar’s government in the mouth."

The appointment of the provisional Islamic government the Imam had promised came

on February 5. Its leadership was entrusted to Mahdi Bazargan, an individual who

had been active for many years in various Islamic organizations, most notably

the Freedom Movement (Nahzat-i Azadi).

The decisive confrontation came less than a week later. Faced with the

progressive disintegration of the armed forces and the desertion of many

officers and men, together with their weapons, to the Revolutionary Committees

that were springing up everywhere, Bakhtiyar decreed a curfew in Tehran to take

effect at 4 p.m. on February 10. Imam Khomeini ordered that the curfew should be

defied and warned that if elements in the army loyal to the Shah did not desist

from killing the people, he would issue a formal fatwa for jihad. The following

day the Supreme Military Council withdrew its support from Bakhtiyar, and on

February 12, 1979, all organs of the regime, political, administrative, and

military, finally collapsed. The revolution had triumphed.

Clearly no revolution can be regarded as the work of a single man, nor can its

causes be interpreted in purely ideological terms; economic and social

developments had helped to prepare the ground for the revolutionary movement of

1978-79. There was also marginal involvement in the revolution, particularly

during its final stages when its triumph seemed assured, by secular,

liberal-nationalist, and leftist elements. But there can be no doubting the

centrality of Imam Khomeini’s role and the integrally Islamic nature of the

revolution he led. Physically removed from his countrymen for fourteen years, he

had an unfailing sense of the revolutionary potential that had surfaced and was

able to mobilize the broad masses of the Iranian people for the attainment of

what seemed to many inside the country (including his chosen premier, Bazargan)

a distant and excessively ambitious goal. His role pertained, moreover, not

merely to moral inspiration and symbolic leadership; he was also the operational

leader of the revolution. Occasionally he accepted advice on details of strategy

from persons in Iran, but he took all key decisions himself, silencing early on

all advocates of compromise with the Shah. It was the mosques that were the

organizational units of the revolution and mass prayers, demonstrations and

martyrdom that were - until the very last stage - its principal weapons.

* Source: coiradio.com