Residence in a non-Muslim land was no doubt experienced by Imam Khomeini as

irksome, and in the declaration he issued from Neauphle-le-Chateau on October

11, 1978, the fortieth day after the massacres of Black Friday, he announced his

intention of moving to any Muslim country that assured him freedom of speech. No

such assurance ever materialized. In addition, his forced removal from Najaf

increased popular anger in Iran still further. It was, however, the Shah’s

regime that turned out to be the ultimate loser from this move. Telephonic

communications with Tehran were far easier from Paris than they had been from

Najaf, thanks to the Shah’s determination to link Iran with the West in every

possible way, and the messages and instructions the Imam issued flowed forth

uninterrupted from the modest command center he established in a small house

opposite his residence.

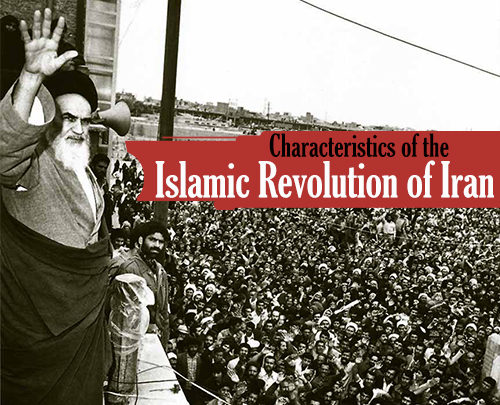

Moreover, a host of journalists from across the world now made their way to

France, and the image and the words of the Imam soon became a daily feature in

the world’s media.

In Iran meanwhile, the Shah was continuously reshaping his government. First he

brought in as Prime Minister Sharif-Imami, an individual supposedly close to

conservative elements among the ulama. Then, on November 6, he formed a military

government under General Ghulam-Rida Azhari, a move explicitly recommended by

the United States. These political maneuverings had essentially no effect on the

progress of the revolution. On November 23, one week before the beginning of

Muharram, the Imam issued a declaration in which he likened the month to “a

divine sword in the hands of the soldiers of Islam, our great religious leaders,

and respected preachers, and all the followers of Imam Hussein, Seyyed al-shuhada’.”

They must, he continued, “make maximum use of it; trusting in the power of God,

they must tear out the remaining roots of this tree of oppression and

treachery.” As for the military government, it was contrary to the Shari’ah and

opposition to it a religious duty.

Vast demonstrations unfurled across Iran as soon as Muharram began. Thousands of

people donned white shrouds as a token of readiness for martyrdom and were cut

down as they defied the nightly curfew. On Muharram 9, a million people marched

in Tehran demanding the overthrow of the monarchy, and the following day,

‘Ashura, more than two million demonstrators approved by acclamation a

seventeen-point declaration of which the most important demand was the formation

of an Islamic government headed by the Imam. Killings by the army continued, but

military discipline began to crumble, and the revolution acquired an economic

dimension with the proclamation of a national strike on December 18. With his

regime crumbling, the Shah now attempted to coopt secular, liberal-nationalist

politicians in order to forestall the foundation of an Islamic government. On

January 3, 1979, Shahpur Bakhtiyar of the National Front (Jabha-yi Milli) was

appointed prime minister to replace General Azhari, and plans were drawn up for

the Shah to leave the country for what was advertised as a temporary absence. On

January 12, the formation of a nine-member regency council was announced; headed

by Jalal al-Din Tihrani, an individual proclaimed to have religious credentials,

it was to represent the Shah’s authority in his absence. None of these maneuvers

distracted the Imam from the goal now increasingly within reach.

The very next day after the formation of the regency council, he proclaimed from

Neauphle-le-Chateau the formation of the Council of the Islamic Revolution (Shaura-yi

Inqilab-i Islami), a body entrusted with establishing a transitional government

to replace the Bakhtiyar administration. On January 16, amid scenes of feverish

popular rejoicing, the Shah left Iran for exile and death.

What remained now was to remove Bakhtiyar and prevent a military coup detat

enabling the Shah to return. The first of these aims came closer to realization

when Sayyid Jalal al-Din Tihrani came to Paris in order to seek a compromise

with Imam Khomeini. He refused to see him until he resigned from the regency

council and pronounced it illegal. As for the military, the gap between senior

generals, unconditionally loyal to the Shah, and the growing number of officers

and recruits sympathetic to the revolution, was constantly growing. When the

United States dispatched General Huyser, commander of NATO land forces in

Europe, to investigate the possibility of a military coup, he was obliged to

report that it was pointless even to consider such a step.

* Source: coiradio.com