February 11, 1979

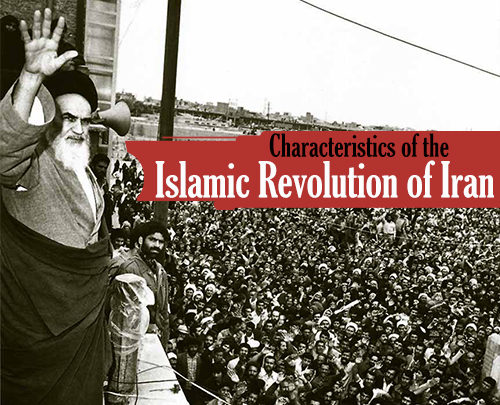

On the first day of February, 1979, an Air France jet touched down in Tehran

carrying a famous passenger on a journey of historic importance. When that

passenger emerged from the plane, he looked on his native country for the first

time in nearly 15 years. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini had been in exile since

1964, and now he was returning with a single aim in mind.

It was the same goal that had driven the last several decades of his life: to

destroy the American-backed, secular government of Muhammad Rida Shah Pahlawi

and found an Islamic state.

He did not have to wait long. By the time he got to Iran, the Shah had already

left the country, bowing to extreme political pressure. In his place, a moderate

politician named Shahpur Bakhtiar had assumed the duties of prime minister and

head of state. By February 11, only 10 days after the ayatollah’s return—and 27

years ago today—Bakhtiar and the other remnants of the Shah’s government had

been chased from power, and a provisional government backed by Khomeini had

assumed control of the country. Few events since have had such grave

repercussions for the United States.

Born in central Iran in 1900, Khomeini was nearly 80 when he returned in

triumph. His conflict with the shah stretched back over decades. Before the

1950s he had been generally satisfied to advance his religious convictions by

teaching young scholars at the Faiziyeh Theological School, in Qom, Iran,

training them to follow his mystical, ascetic ways. In 1951, however, he watched

with interest as the reformer Muhammad Mossadegh garnered vast popular support

for a nationalistic approach to government. When Mossadegh was deposed by an

American-backed coup and the shah’s personal rule was restored, Khomeini

understood that there remained a latent demand for sterner leadership.

Gradually he waded deeper into politics, surreptitiously meeting with activist

clerics and learning from their experiences. And at the beginning of the 1960s

he became the most visible antagonist of Shah Pahlawi. In a series of

confrontations with the government, he spoke forcefully against the shah, his

accommodating attitude toward the West, and his policy of directing Iran’s oil

resources toward the United States and Britain.

The rivalry between the two leaders came to a head in 1963 and 1964. In 1963 the

Shah sent troops to Qom to storm the religious academy where Khomeini taught.

Until then Pahlawi had successfully undermined his opponents in labor unions and

political parties but had left the clergy largely untouched, even though some of

them harbored equally defiant sentiments. The government soldiers meant to

stifle Khomeini’s students’ revolutionary tendencies, but they had the opposite

effect. The killing of two unarmed students ignited widespread public anger.

Forty days later Khomeini led huge crowds in rituals of mourning for the slain

students, and the gatherings broke into ongoing riots.

The following year the situation deteriorated even further, as Khomeini came to

the forefront of Iranian politics by leading rallies denouncing a military pact

with the United States. In November it became clear to Pahlawi, his ministers,

and his American allies that Khomeini’s activism must stop. Faced with a number

of options, among them covert assassination, the shah chose to banish Khomeini

from Iran. On November 4, 1964, he and his son were taken to the airport in

Tehran and flown from there to a Turkish air force base.

Khomeini spent about a year in Turkey but soon received permission from Iraq’s

government to move there. He lived in the holy city of Najaf, Iraq, until 1978,

his hostility toward the shah and the United States unabated. Sympathetic

activists smuggled his writings into Iran, copied them, and distributed them

among the populace—especially among students. Understanding the menace Khomeini

still posed, the shah pressured Iraqi President Saddam Hussein to expel him.

When Hussein complied, Khomeini left for Paris; there, in the first weeks of

1979, he prepared to return home.

As Iran fell into economic crisis and popular opposition to the shah mounted,

Pahlawi, who had been diagnosed with cancer in 1974, ceded control of the

Iranian government to the moderate Bakhtiar and left for Egypt. By the time

Khomeini returned to Iran, Bakhtiar’s government was tottering. Less than a week

after his homecoming, Khomeini formed a provisional revolutionary government in

direct opposition to the regime. When the military refused to crush Khomeini’s

uprising, Bakhtiar’s government fell apart. On February 11, Khomeini’s followers

declared victory on Iran’s state radio.

With his fundamentalist regime in place, Khomeini adopted a militantly

anti-American stance on foreign policy. On November 4, 1979, student followers

of his seized the American embassy in Tehran, taking 66 American spies and

dealing a fatal blow to the struggling Carter presidency. In 1980 the

Ayatollah’s government mounted a massive invasion of neighboring Iraq, leading

to the protracted and bloody struggle that defined much of America’s involvement

in the Middle East during the 1980s. Though Khomeini himself died in 1989, his

followers control Iran to this day and continue to embrace his antagonistic

attitude toward the United States and the West.

In 2005 Iran elected a new president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Before he became

president, Ahmadinejad was mayor of Tehran, but before that he was a foot

soldier in Khomeini’s fundamentalist revolution. Five former hostages have

identified him as one of the students who seized the American embassy. According

to one journalist, the Iranian president’s political philosophy can be stated

simply: “Ahmadinejad sees his role as promoting the same platform of global

jihad he has been actively participating in since 1979.” And the latest battle

over Iran’s nuclear capability is a strong sign of that. Thus Khomeini’s seizure

of power influences global politics to this day, and the heirs of his revolution

continue to threaten the interests and security of the United States.